For all the excitement about the explosive pace of progress in AI and technology that many readers of this blog will share, there’s an undeniable feeling of uneasiness: things are perhaps moving too fast and having second order effects across society that we are just beginning to truly appreciate.

The Exponential Age is one of the best books I’ve read in a while. It’s a bold exploration and call-to-arms over the widening gap between AI, automation, big data and other emerging technologies, on the one hand, and our ability to deal with their impact, on the other hand. Those technologies are growing at an exponential pace but our society is not. This “exponential gap” explains many problems of our time – from political polarization to ballooning inequality to unchecked corporate power.

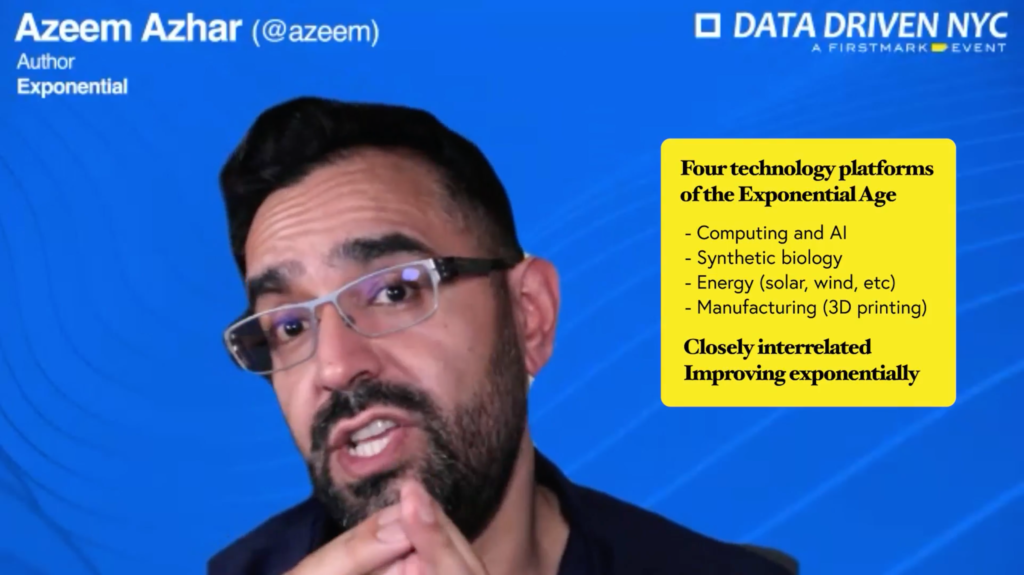

It was a real pleasure to host at our most recent Data Driven event its excellent author, Azeem Azhar, an entrepreneur, investor, renowned technology analyst and host of the global tech podcast Exponential View.

Below is the video and full transcript.

(As always, Data Driven NYC is a team effort – many thanks to my FirstMark colleagues Jack Cohen, Karissa Domondon Diego Guttierez)

VIDEO:

TRANSCRIPT [edited for clarity and brevity]

[Matt Turck] Today we’re going to talk about your book, The Exponential Age, which was published just a few months ago, which I’ve really, really enjoyed. I have to say, it’s a wonderful framework to make sense of a lot of those confusing trends that we all sort of sense, but it really packages everything in a way where it all makes sense. The book really offers a really insightful full glimpse into the future. I highly recommend the book and am excited to talk about it today.

Thank you.

What is The Exponential Age and why is progress accelerating?

Well, The Exponential Age is where we are now. Perhaps it’s easiest to explain by explaining where we’ve come from. In the book, I argue that a lot of the world, certainly up to the last five or six years, is built on the after effects of three major technology platforms that emerged at about the same time in the 1890s. Those technologies are energy, transport, and communication, the internal combustion engine, electricity and the telephone. Independently around that time, the sort of 1880s, 1890s, and then becoming mainstream in advanced Western economies by the 1920s, these technologies created the clock speed and the design patterns of the 20th century. We lived in big cities. We thought that oil was really, really important. We used mass production and manufacturing that was pioneered in the modern way by Henry Ford.

So technologies connect to society most broadly, but industry structure, economic imperatives, social behaviors, social mores, and the contention I have today is that we are at a point and just past a cusp where there are new general purpose technology platforms that are going to supplant the ones that define the 20th century.

Those are the broad technology platforms of computing and artificial intelligence which is the most important of these, of what’s happening in the fields of biology, particularly when it intersects with data driven approaches. What’s happening in the field of energy and what’s happening with manufacturing. These four technology platforms are powerful and broad, but they’re so closely interrelated. One is feeding into another, you see techniques in one appearing in another. And critically they are improving at that rate that makes venture capitalists excited up and to the right, double digits.

And by improving, I mean on a price performance basis, they get better by 10%, 20%, 40%, 50% per annum compounding. And of course the best example of that is Moore’s Law with the continued miniaturization of silicon chips and effectively getting more power for the same dollar that we spend. But we see these similar effects in the decline in solar photovoltaics, in wind turbine pricing, in the cost to sequence a human genome, in the price performance of 3D printing of different types, in the cost to synthesize artificial genes. That’s why I called it The Exponential Age, because that mathematical process of compounding interest is an exponential one.

You were also saying that we are as humans particularly ill equipped to really understand that concept of exponential growth. And in some ways we’re still at the beginning of this curve.

I think we’re definitely at the beginning, we don’t see exponential processes that we can witness in the real world. By real world, I mean, sort of outside of the world of TechCrunch and Twitter. COVID and its moments of exponential growth at the different waves was the first time that many people would’ve seen this outside of technology. And there aren’t processes like that we see.

I dug into this question quite a lot to say, is it really true that humans are not good at generally understanding exponential processes? The research is not great, but the theory is kind of well understood, which is that the process of evolution selects for traits that make us successful. And in a world where we mostly see linear processes, the lion is running at us at… Matt, I know you’re European. Can I use miles an hour?

Yes!

The lion is running at us at 28 miles an hour. That is a linear process. And the person who understands that survives. The person who thought of it as an exponential will not survive. They will get exhausted. So there are lots of reasons why, from an evolutionary perspective, exponential understanding would’ve been selected out. But of course we’ve created these technologies that are marching down a learning curve that are now exponential. And in this new digital data driven world that we’ve built, we see exponentiality all around us. And most of us, and I suspect the people on this call are likely to be in the exception category are not well selected, and they’re not well trained in dealing with the ramifications of that exponentiality.

Related to this, a fundamental part of the thesis in the book is that there is a chunk of society, which is lagging behind and that’s what you call the exponential gap.

Yeah absolutely. And the reason is that, so what is society? Society is a kind of complex multidimensional multi-layered group of more formal and less formal arrangements. It ranges from the tax laws or the DMV regulations through to just when do you cross the road, or do you give way to pedestrians – something we do, I know in the UK, but doesn’t happen as often in other parts of the world.

Those are institutional arrangements and they make life easier to live. Because we know what the rules are. We know how we need to behave. But they adjust very, very slowly and they adjust slowly for lots of good reasons. If institutions adjusted very quickly at the speed of the latest viral meme, life would be unbearable. Because the laws would be changing every 17 seconds. So that almost in the design in this system, there is going to be a chasm between the potential of the technology and the rules that are designed to sort of manage life. What’s interesting is that it’s really just been in the last 10 or 15 years, where that pace, the difference in that pace has been so rapid that the gap becomes more and more present.

In some cases, a gap creates incredible profit opportunity. That’s where Jeff Bezos used to say your margin is my opportunity. Well he might also have said the exponential gap creates my opportunity, but it also bites us on the other side because we rely on institutional agreement and regulation and societal norms to make life manageable. And what we’ve seen, particularly in our politics, but also in the increasing strength of certain companies in industry sectors or the increasing friction in international relations is that these technologies tend to end run the shock absorbers of life.

One of the characteristics of this exponential age is the rise of what you call the unlimited company. What others call the superstar companies. What are those, and why are they growing so fast and becoming so dominant? And I guess, why are they so different from the previous market leading companies?

When I started to learn about business in the early to mid-90s, the general rule was that companies could only get to a certain size because competition would eat away at them. And that there were a few little aspects. So first of all, one was that if you had a successful company, a new competitor could come in and compete away at the margins in some other way. The second is that managerially things would get too complicated. This was sort of Ronald Coase’s insight back in the 1930s, that effectively, at some point a company would get so big, that it was so expensive to do things internally, it’d be cheap ago to the market. And the third was this idea that companies would have increasing costs. So the 10,000th ton of steel that a car company bought would be more expensive than the 500th ton. And at some point it just wouldn’t be profitable to source that.

So there was this idea of a 40/20/10 market. The top company had 40% market share, the second would have 20, and the third would have 10. In these exponential markets, you don’t see that. So Google is number one. And some of us can name Bing and a handful of people DuckDuckGo. But who’s the fourth biggest search engine in the US. I mean, I don’t know. The reason for that is to look at those three things that slowed companies down in the past, the force of gravity. I think the one that’s most important is the one that you sort of wrote the sort of critical blog post on about six years ago, seven years ago, which is the data network effect.

The fact that data network effects do construct a flywheel that becomes a second flywheel on top of the traditional customer network effect. And what that means in is your ability to actually serve products that your competitors simply can’t serve and actually can super serve niches. I mean, that’s the sort of power of the data network effect. That by seeing a lot of people, and by having these new AI systems like deep learning that can operate in incredibly high dimensionality, you can construct niches and segments and segmentation leads to price discrimination, and it leads to hyper loyalty.

All the things that sort of MBA students get taught are really important in their marketing modules. That combination of sort of the data network effect with these new AI techniques, I think constructs a resilience to these businesses. Then there’s some other issues around how IT and KPI-driven management and automation in the back plane of companies has allowed them to push past the traditional Coasian barrier, that Coasian boundary being, how far can managers actually manage a team.

The thing I think that brings us home is that you look at a company like Google or Apple, or even Facebook, which has had like the shittest year ever in the last year, but it’s still 10 times better a year than they deserved. Facebook still grew 20 plus percent top line, despite being massive. General Motors was not capable of doing that from the 1970s. So Facebook still grows and still, despite regulatory hatred, customers leaving them, and so on becomes more profitable and decides to launch a new platform. It’s like the boss mode of a horrible arcade game where the thing gets stronger and stronger every time you punch it. What’s true for Facebook, which is the weakest of the big tech companies is as true for Apple and Google and everyone else.

As an example of exponential gap, you say in the book that the basically antitrust law is coming from a completely different age at this, and is completely ill-equipped to handle a superstar company.

The assumptions were completely different. They were very short term. The assumption was that a monopolist would price gouge because they’ll get their prices. And what we discover with someone like Jeff Bezos is he was perfectly willing not to have profits for decades in order to bet on the future. That is where the antitrust law has fallen afoul certainly in the US, because it was focused fundamentally on cost to consumer. But we know that there are costs that are embedded elsewhere in the system. So we know that if you are on Amazon’s platform, they will be looking at what products you are selling and they’ll figure out whether they should build an Amazon basics by looking at the data that competes with you. We know that if you are Uber, a driver on Uber while it’s great for the consumer, the driver who is a participant and a stakeholder in that platform is totally commoditized and has no way of differentiating themselves in the market.

And so there are these costs that ultimately the purpose of an economy is to serve society and incentives and profits are one of the mechanisms by which economic entities can therefore serve society. When it breaks, it breaks for everyone. So one of the people I talk about in terms of her perspective is Lina Khan who’s now running the FTC. She wasn’t when I wrote the book, her ideas of saying, let’s reframe how we think about where harms occur and what it is for these things to function correctly. I think she was as good a choice as could possibly have been made, frankly, but she’s one, and I don’t think the politicians, certainly I can speak for those in the UK have necessarily kind of cottoned on exactly what kind of changes are required.

So in the same vein one of the most obvious and talked about impact of the rise of this exponential technologies, is concerns around the labor market and what it means for people in the jobs. What is your view on the impact of AI, robotics, automation, and so on and so forth on labor?

It’s funny when I wrote the book and I started the research, all of the analysts or not all of them, many of them were talking about the robot jobs apocalypse. Of course, here we are after the pandemic and every employer is desperate to hire, wages are rising really, really rapidly and robots still can’t open doors. So I think the reality is that the data seems to show is that companies who invest in robotics, automation, AI, grow. But it’s companies that don’t, that shed the jobs. So where there are job losses, it’s not because Marvin the paranoid android showed up one day in FirstMark and was more skeptical about everything than you and you lost your job.

VC’s cannot be automated just to be clear.

No, no, of course not. Because it’s an empathy game. It’s a game about understanding the founder and their tough journey and liquidation preferences don’t come into it.

We’re just adding value.

Adding value, right. So the way that automation seems to take jobs is that ultimately companies fail, and so the difficult part of the story is that companies who invest in automation just seem to compete better. The question is, why is that? I think the reason is that automation, AI, robotics, these are difficult things to get your head around. It’s difficult to implement. It’s incredibly motivating if you do it successfully. It shows employees that you care about the future. That is a recipe for high performance, for a performing team. High performing teams, outperform low performing teams and in the Schumpeterian market, the low performing teams go out of business. I suspect that’s the way, and I sort of argue it in that way in the book that we should think about automation. It’s so difficult. It’s a risk, it’s hard to get. You have to motivate people. The managers who can do that well, and therefore are the survivors of automation out compete the crappy managers who don’t invest in these technologies.

A really interesting trend that you highlight in the book, which is the return to local. So in the world where we all grew up in the world is flat type trend towards globalization will only compound and accelerate. This seems to be very different. So what is it, and why is that happening?

Lots of the technologies that we’ve had have been technologies that shrink distance, I mean, the car strike distances, and what we got was the first city of 10 million, which was New York in 1936. Then we got Scottsdale, Arizona and Phoenix, which are kind of massive. So what’s going on there? So in general, what we’ve been able to do by reducing the cost of communication through the car and the telephone and the internet is expand supply chains and distance. With these new exponential technologies, what we’re able to deliver is locality. So solar power, wind power, virtual power plants, and batteries made up of the batteries in electric vehicles, all enable local rather than national provision of one of our key inputs, which is energy. So you don’t need to spend $3.4 billion on a 600 megawatt coal plant. You can just, as they have in South Australia, wait for householders to put solar panels on the roof, and feed into the grid.

A similar thing is happening on the side of food. So of course your participants will be familiar with bioreactors and lab grown meats, but also high intensity urban farming, which is fundamentally a game of data, genomics, robotics, and AI, will for the first time, since we actually had cities and from 9,000 BC allow cities to be self-sustaining in their food. And 3D printing, while it’s still kind of weird and small, will also take up some of the slack for the production of either finished manufactures or parts. So I think what you see there is a set of headwinds against this idea of really, really deep and extensive and fragile global supply chains. Now, there were other angles to this, which I didn’t put in the book at the time that were to do with economic security and also national security questions and questions of resilience and technology competition, particularly around semiconductors.

But those also are headwinds against the idea of sort of these global flows. The counterargument to that was, but look at the complex supply ecosystem around semiconductors. Do we really think that what happens in TSMC could just happen in Hoboken or in Ghent? No, it’s got to happen in Taiwan because it’s not just TSMC. There’s a whole bunch of chemical suppliers and semiconductor wafer washers, and there’s an established sort of logistics network there. And that’s true at the really, really hard end. That’s quite hard to move. But what we’ve discovered is the imperative to construct resilience, post-COVID and post-geopolitical competition has accelerated and strengthened this trend of the return to the local.

To the point of geopolitics, what does that mean? There’s something that you call the new world disorder, which sounds pretty ominous. What is that?

Yeah, it’s pretty shitty. So the core idea in the book is that prices are coming down in a way. And what we’re doing through, through new technologies, whether it is cyber warfare or disinformation or drone based warfare, is that we are reducing the cost almost to zero of certain types of conflagration. So once something reduces in price, I mean, we know this as investors. The price of AI comes down because of Moore’s Law and more companies use AI. So the price of being an annoying player on the international stage falls to zero, because you don’t have to roll a tank across the border. You’ll see much more of this. That’s not to say that tank based warfare as we are sadly going to learn over the next few weeks is not going to exist, but it does mean that the way in which you do the buildup can change.

What we’ve seen, certainly in this kind of Ukraine conflagration is a really aggressive, but quite unsuccessful compared to other things, disinformation campaign, which is one of the strategies you’d expect a country to use as well as cyber attacks. What you are doing there is you are using disinformation to create a constant sense of distrust so that your adversaries are fighting amongst themselves. You’re using cyber attacks to debilitate the day to day functioning of the nation. So people are worrying about other things, and then you let your tanks roll in. That recipe is increasingly going to be tried and tested. It creates enormous opportunities actually for entrepreneurs who are thinking… I mean they’re not all the NSO group, but entrepreneurs who are thinking, how do we build resilience? How do we help societies be able to defend both against the disinformation and against the cyber attacks?

So where does it all leave us? How do you see the next five years? And then the next 20, where do you think that’s all going? By the way, if you could also let me know where I should invest while we are at it.

I follow where you guys are investing.

That may not end up well. If we follow each other.

I think there’s a set of technologies that are really on that cusp of being sort of amazingly interesting. I think you see the synthetic biology arena, that overlap between data driven biology and machine learning, starting to come to fruition. Now what we’re doing is we’re struggling on the scaling. So no one has really got the scaling right. But more and more people are getting the front end right. The scaling will therefore follow. We’ll figure out that it’s all about having custom bioreactors for whether you are making a therapeutic versus a meat versus a material. And that will all start to fall into place. But I think that that is the sort of most ripe, really interesting technology.

I also think that you’re seeing over that 20 year timeframe, real breakthroughs in two super hard technologies that will rely on more ancillary technologies – quantum computing and nuclear fusion, that will need all sorts of breakthroughs in material science, amongst other things that we could expect to see. But the other thing to just think about is that in the decade between 2011 and 2021, just look at Germany, because I spoke to the sort of top people at Deutsche Telecom recently, the amount of data across Deutsche’s mobile network increased 300 fold over the last 10 years. And so the question is over the next 20 years, which is two lots of 10 years. If it grew at the rate it grew over the last decade, it would grow 90,000 times, 300 squared. So if you think it’s going to be less than a 90,000 fold growth, you have to have quite a strong argument as to why that’s the case.

90,000 I think should be your base care. In reality, maybe it’s going to be much more than that. Then I think we can start to ask the second and third order questions, which is, what the hell are we doing with all of that data? What’s going to be happening? What will be the applications using it? What will be the end user devices? And then a whole set of things come up. How are we going to manage this all? How are we going to store it? How are we going to do over the air updates to a trillion devices kicking around in the cloud? So the thing is, I don’t think it stops because I’m not sure I see the natural physical limits at this point as to why it would necessarily stop.

Well, that feels like a very interesting point to call this conversation a wrap. Thank you so much. The book again, The Exponential Age is super interesting. I would highly recommend it. Where do people learn about your work? Where do they follow you, your newsletter? How do they do all of that?

You can find me on Twitter. I’m @Azeem, A-Z-E-E-M. The newsletter is just Exponential View, which you can put into Bing.

Or whatever the fourth search engine is.

Yeah. Whatever the fourth is.

Which nobody knows. Wonderful. Cool. Well look, thank you so much. Really enjoyed it. Appreciate your joining us tonight from London, late into the evening, way past your bedtime, as you said. Thanks for sharing all of this with us. This is terrific.

It’s been my pleasure, Matt. Thank you so much. And thank you for all the sort of inspiration in your blog posts and your funny tweets over the years.